This is the first of three articles on the history of the Chinese script, and inspirations for the system of writing I use in my paintings. This article is a historical overview and introduces some linguistic concepts.

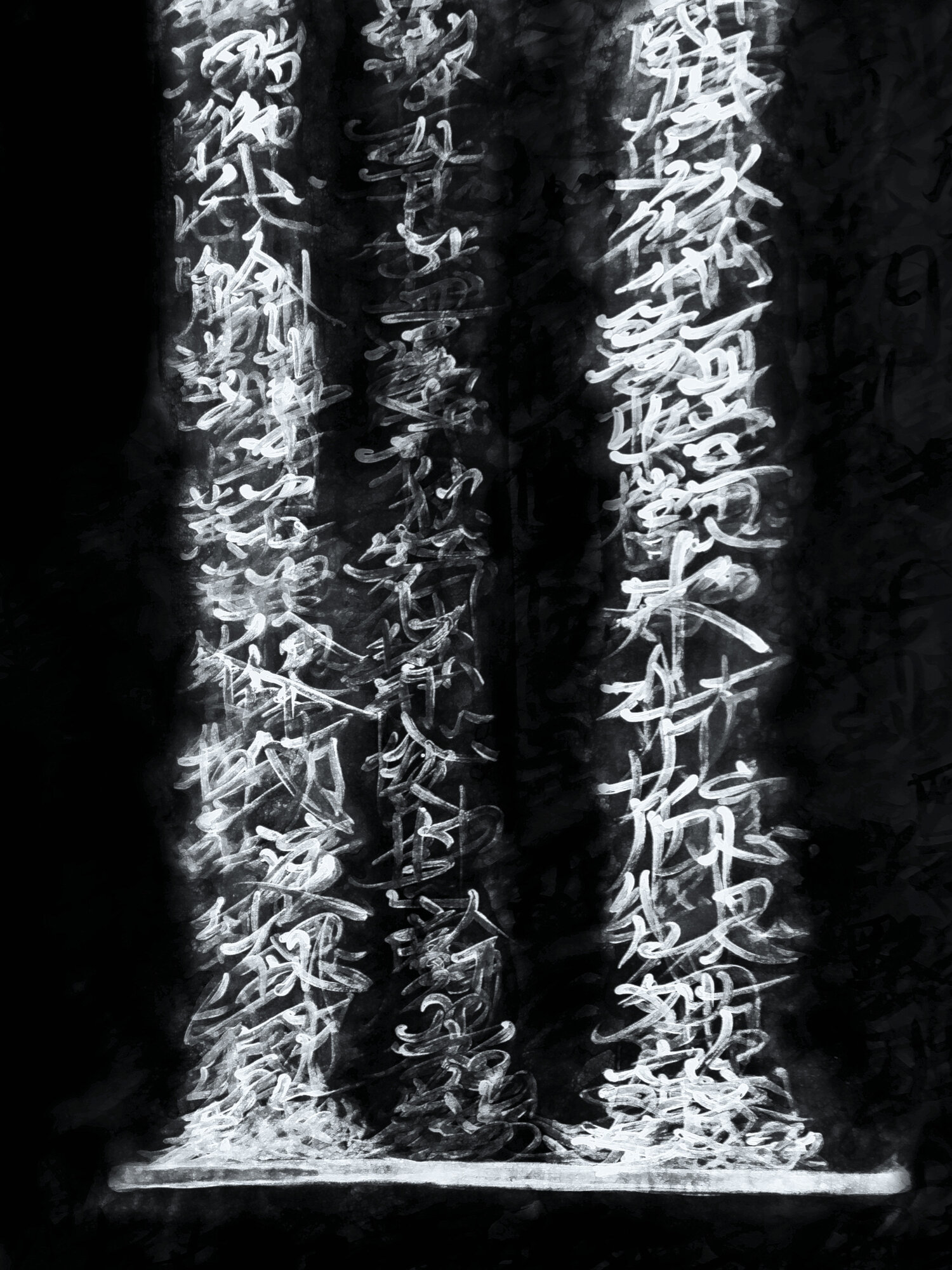

In my paintings there are Chinese characters embedded everywhere. No matter how abstract, all the forms are built from overlapped writing. The writing uses a combination of traditional characters overwritten using a system I created to phonetically represent the Toisan dialect. I was born in Oakland California. My mother and her family are from Toisan in Guangdong, China. Their immigration and subsequent integration into American society led to a drastic language gap between our generations. As a child I spoke some Toisan and Cantonese, without realizing the distinction between the two. Like many immigrants, my mother’s family was preoccupied with economic stability, all other things being secondary. Cultural continuity in something like language, depends on it’s use being a daily fact of life. The desire for mobility and achieving the American dream did not necessarily benefit cohesion with our extended family. With the absence of a community and relationships to reinforce the use of Toisan and Cantonese, most of my native language skills quickly faded at a young age.

The family story felt most evident in my relationship with my mother, and our complicated communication. The way we spoke to each other, was coming from different worlds based in sound. Chinese pronunciation uses tone for distinguishing words, whereas English usually uses tone for modifying the meaning of sentences. (For example, the phrase “What are you doing“ could be an inquiry, an accusation, or figurative.) Our speech patterns communicated different connotations. We frequently misunderstood each other, and even when we did, major cultural differences were already ingrained. Reality is big enough to fill many perspectives, but only fluency could relay it meaningfully.

My mother was born in the village where this dialect had emerged over a thousand years, and one generation later, neither me nor my siblings could speak it. The full realization of this loss started me on a path towards learning Chinese, and writing in particular. At that time, my artwork did not intentionally reflect the experiences of my life. The absence of this language in my day to day life was the result of circumstances much larger. Social, political, cultural issues all played their roles, and I’m left with more questions than insights. This language project become an interior activity to understand why my family’s integration happened the way it did.

In writing I realized there was no system for notating Toisan dialect, and I set out to create one. In linguistics, a written system is called an orthography. For languages using the Latin alphabet, the nuances of speech are orthographically depicted by the letters, punctuation marks, and diacritics (for example: ~ in Niña). These symbols are referred to as graphemes, which are abstractions of the phonetic syllables utilized in a language.

The Phoenician Abjad is a possible precursor to most of the world’s alphabetic systems. An Abjad uses alphabet-like symbols to represent consonants, and the reader infers the vowels.

Many orthographies likely derived from Phoenician, and traveled an impressive distance, far outliving the Phonecians themselves. Pictured below are scripts from Western Europe to Far North Eastern China, all evolving from a root in what is now Lebanon.

A very large number of languages are written in the Brahmic scripts, which began developing in the 3rd Century BCE. From India they spread throughout Asia: North through Tibet and southeast into the Malay and Philippine Archipelago. It is hypothesized that the Brahmic scripts may have had significant influences from Aramaic, but evidence is inconclusive. Nevertheless, an explosion of orthographic diversity occurs in South Asia.

Concurrent to the development of alphabetic orthographies, were logographic systems like Egyptian Heiroglyphs, The classical Mayan Glyphs, Cuneiform of Mesopotamia, Nsibidi in Nigeria, and Chinese characters. Logographic systems use a single glyph (a collection of symbols) to represent either entire words or morphemes, the smallest meaningful unit of a language; Such as prefixes, suffixes, affixes.

Logographic systems include the oldest known writing systems. When looking at very early Chinese characters, we can observe something fundamental about how human beings perceive and convey conceptualizations of the world.

The Oracle bone script uses symbols which represent real world entities. Perhaps anyone who ever drew rudimentary images in their life, has echoed the cognition that brought about our earliest written languages. Chinese characters today combine both logographic and phonetic elements. There are four categories of character creation methods:

(all below with images)

Pictograms (象形字) – expressing literal concepts like person, animal, water.

Ideograms (指事字) – expressing abstract ideas such as numbers, directions, etc.

Compound (會意字) – associating multiple characters to suggest other meanings

Phono-Semantic (形聲字) – a combination character utilizing symbols with a similar phonetic pronunciation, and a semantic character to indicate meaning. This is the primary system that accounts for 90% of modern Chinese orthography.

It may seem incredible that a logographic writing system persists to this day, given that thousands of symbols are needed to represent a growing vocabulary. But there are practical reasons for not using alphabets. Numerals for example, are logographic. They contain no phonetic information. Though numbers can be written out, performing any kind of mathematics with numbers spelled out alphabetically would be inhumane. Alphabets also limit the readability of a script per language, which is the precise reason Chinese characters have persisted. Spoken Chinese has diverged into several dialects which are mutually unintelligible. The written system has maintained readability through centuries of linguistic changes.

For reasons practical and political, Chinese identity and language is undergoing a kind of homogenization, through standardization of the Mandarin dialect as the official Chinese language. Mandarin itself also divides into regional dialects with varying degrees of mutual intelligibility. Though Chinese characters reflect the significant history, culture, and continuity of the language, it does not necessarily represent the way people speak. Although the different forms of Chinese are classified as dialects, they could be considered different languages. Such as with languages derived from Latin (Italian, Spanish, french, Romanian, etc).

Toisan is part of the Yue branch of Chinese which includes Cantonese. These languages preserve sounds from classical Chinese, and when reading Tang dynasty poetry (618 – 907 CE) in modern Yue dialects, many words still rhyme. Whereas in Mandarin, pronunciations have diverged significantly. The Yue languages are believed to have began developing in 214 BCE, when Qin dynasty forces invaded the area that is today Guangdong and Guangxi provinces. Yue was the name given to the local people, written in classical Chinese as The “百越, Bak Yuht“ or 100 Yue. A kingdom of tribes who would eventually disappear into assimilation with Han culture following war, and waves of migration into their territory. Today's Southern Han Chinese, Yue-speaking population is descended from both groups. The colloquial layers of Yue dialects contain elements influenced by the Tai languages formerly spoken widely in the area and still spoken by people such as the Zhuang.

Periods of war, civil unrest, and overall instability, motivated Han Chinese peoples to move south. By the time of the Jin Dynasty (266 - 420 CE) a distinct local identity was already entrenched enough that newer waves of migration were met with hostility by the local population. These later migrants were called Hakka by the locals. Hakka means Guest families in Cantonese, and was not meant politely. In turn, the peoples appropriated the Hakka label and settled permanently. Their conflict would become a cataclysm during the Hakka-Bundei Clan wars. It is estimated that a million people died, and widespread devastation occurred in villages throughout the region, but particularly in “四邑Sei Yap”, the four counties which includes Toisan. This conflict, along with the Taiping rebellion, caused the mass emigration of peoples from Guangdong during the transition between the 19th and 20th centuries.

Royal courts had fled to Southern China with vast entourages of Clans who over time went from riches to rags, and back again in cycles so long to have been forgotten by most of their descendants. Peoples historically connected to the same origin along the Yellow river, who both fled violence into Southern China in search of a better life, would go on to destroy one another. They and their descendants would flee the area for Cities or leave China altogether. For myself, I was unaware of any of this history until researching. Family recollections of my great grandfather’s life point to economic reasons for leaving China, but not much detail on the circumstances. Regardless of where we come from, some cyclical history has played out, and predetermined the circumstances of our lives.

With language we attempt to describe the world and expand our range out from the intrinsic generalities we inherit. It is human nature to depend on our definitions and abstractions. Comprehension requires us to create a model of the world in our minds. But that model cannot match the infinity of reality, and our ability to absorb quality information about the environment requires unprecedented critical thinking skills. The world is exponentially increasing in complexity. Understanding where we have been is essential perspective for where we could go. This being the case, facts are precious, and dialects are self evident facts. They have developed over a long history, and through their phonetic features, vocabulary, and locale, a glimpse of human history can be mapped.

In Part 2, I’ll cover the history of how the Chinese script has been adapted for other languages, and the methods that have been used for recording dialects. With these topics in mind, I’ll introduce the system I devised for Toisan in Part 3.

Note: Most of my sources for this article began with Wikipedia articles. I encourage you to carry out your own research and seek primary sources. I’ve written all material to the best of my knowledge. If there are discrepancies you think I should address, please let me know.